Click here to Last Sunday, driving back to Derbyshire from Chester, I caught Open Book on Radio 3 with Matt Haig talking to Mariella Frostrup about the book that changed his life – Jennie, by Paul Gallico. He spoke of how this touching story about a boy who has an accident, goes into a coma, and then awakens as a cat, had a profound influence on his recovery from depression. Recalling the sweet power of Gallico’s writing in The Snow Goose, I’ve decided that Jennie is a book I must read. As I drove over the rainy hills of Staffordshire, the interview made me think about the first book I remember changing my life. I was on the cusp of adolescence between primary school and high school, and it was early summer. My father, on returning from a fishing trip, gave me a book called Weaver of Dreams, by Elfrida Vipont. I remember him explaining it was about three sisters who wrote novels and became very famous, and their unfortunate brother, who had showed early promise, then failed to live up to everyone’s expectations. It was a slim green hardback with a dust jacket of an ink painting of a turreted city, reminiscent of the work of John Piper. I began reading it the same day. Weaver of Dreams is a fictional biography of Charlotte Bronte between the ages of four and eighteen, and I couldn’t put it down. Charlotte’s early life, her closeness to her two older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, who were subjected to cruel treatment and then died at Cowan Bridge School, her return to the parsonage in Haworth, and the unfolding richness of her imaginary world shared with Emily, Branwell and Anne, were brought vividly to life. I was enchanted, and the book was passed round all my friends over the summer months of 1977. I went on to read all the Bronte novels, as many biographies as I could discover, and to learn much of Emily’s poetry by heart. It was Emily I was most in love with, strange, silent Emily, who I later discovered lit up many young lives. For three years I lived a kind of romantic life fuelled by her longing for the Yorkshire moors. Born and living in the city, I too longed for the wildness of the countryside, found city life oppressive and depressing. All my diaries of the time talk of my need for freedom. I’ve scarcely written a poem since, but I became adept at Bronte pastiche, and wish I’d kept those school exercise books, where my English teacher, Mr Smith, had given me top marks and rave reviews. My best friend, Vivien, and I wrote gothic stories set on heather-clad moors, and exchanged notes in tiny handwriting, like the books written by the Bronte children. I took myself extremely seriously in a way only possible during adolescence – and whilst it seems amusing now, I know that in some way I was sustained by those three extraordinary sisters during my own troubled years – the poetic power of their imaginary world, their isolation, their writing.

0 Comments

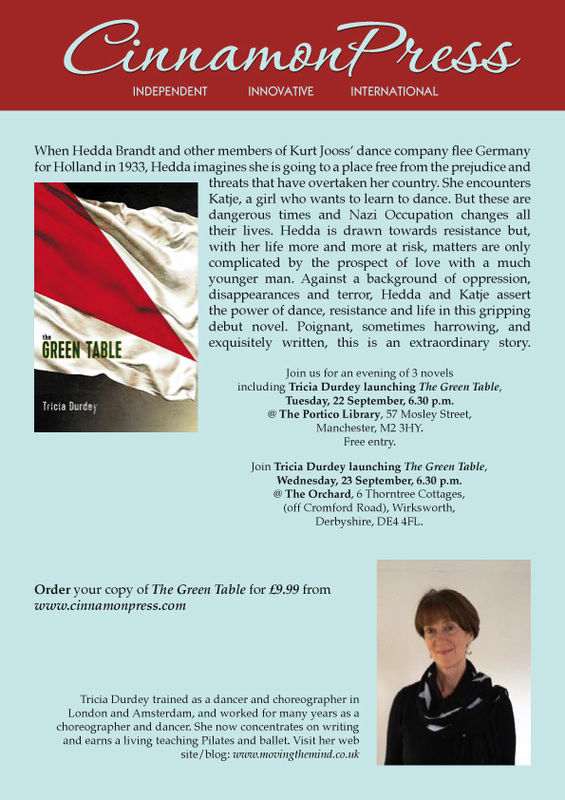

There’s a form of dance improvisation where, working with a partner, a dancer closes her eyes and moves, or dances for as long as she wants. Her partner sits quietly and witnesses. Later the witness becomes the dancer. There’s something extraordinary about this form in the way it fires the imagination, the way the dancer inhabits and embodies her interior world. It’s not at all the same without a partner – there’s something about the presence of a benign witness that creates a shared and mysterious language. My novel, The Green Table, has now been launched, in Manchester Portico Library – a breathtakingly beautiful building, and in my movement studio in the orchard at home. The celebrations came at a time when the welfare of my aged parents was of paramount importance, and I wondered if I would find the strength to focus on anything else. But I was much encouraged, and in some sense brought back to life, by the dedication of my publisher, Jan Fortune, and the warmth of family and friends. The orchard looked beautiful in the soft September dusk, the smoking bonfire, light rain falling through apple trees lit by fairy lights. I was amazed by how many people could crowd into my studio, where I teach a maximum of five people, and what a fine venue it was for the reading. And now The Green Table is out of my hands, and in some way I am reminded of my times dancing, eyes closed, sensing my partner watching. The characters I know so well, the world I spent hours imagining and recording, now live in my readers’ imagination. There will be people who love the book, and others who don’t – all that is beyond my control now. I’m glad to let go. What next? I’m certain, even in the midst of family crisis, that a sequel to The Green Table waits like a kind of research project, and I’m curious, wondering what I’ll discover about post-war Europe, and what happened to my characters after 1946. It also seems important to give attention to the craft of writing, and to that end I’ll draw up a reading list later this weekend – all those classic novels I’ve never read. I’m a slow reader, and writer, and it will take a long time – years of research, reading, and writing. I’m looking forward to it all – immensely. Photographs by George Peck - September 23rd Orchard Studio, Thorntree Cottage

My friend, Sarah Butler, talked of the deep happiness she felt when her first novel, Ten Things I’ve Learnt About Love, was launched two years ago. Now with only days to go before the launch of The Green Table, I know that I’d once have felt the same. As it is, much has happened in the last ten years since I wrote the first page, on an Arvon Foundation writing course led by Celia Rees and Jan Mark at Lumb Bank. Both tutors encouraged us to begin a new work over those four days in September, and I remember sitting in a writing hut in the garden, overlooking the steep wooded valley and talking to Celia about Amsterdam and the Nazi Occupation, and how I wanted to write something about a young girl who was determined to dance. As I began to write, I remembered Hilde Holger, a Viennese Jewish dancer I trained with briefly in a basement in Camden Town. She was a very old lady, fiery and passionate, who had survived, and danced despite the daily threat of being discovered by the Nazis. I heard her voice shouting at us as she banged her tamba, and the first scene wrote itself. The novel for teenagers was written within a year. I loved it wholeheartedly for a short while.

It’s a long time ago. There have been many disappointments and I’ve struggled to be patient, to keep on working regardless of outcome – success or failure. I’ve drafted two versions as a book for teenagers, and a further final draft for adults. I’ve learnt how to refine and edit and take criticism, and now the launch feels like only another stage – albeit a happy one, in a long continuum. The book arrived from my publisher only days before a crisis with my very old parents that has cast a long foreshadow over the summer. Holding it in my hands I felt nothing but a distant wonder that at last, after so many edits, redrafts, and proof readings there it was, with its fine cover designed by Adam Craig. I showed it to my father only days later, as he lay in bed with his broken hip. I will read it, he said, but not now. I know he never will. He was a great reader and took pride in my work but it has come three years too late for that. Those who have cared for old parents will know the terrain. In the last two weeks my heaviness of heart has been balanced by moments of wonder – watching the crows preening on the rooftop, a shimmering stand of golden poplars – that seem extraordinary and beautiful. How at the hardest times, the brilliant moments sustain. Now I look forward to my book launches in Manchester and Wirksworth, and hope it’s the beginning of a new phase in my life as a writer. When I first moved to Wirksworth, in my early twenties, two of the first people I met were Bernard and Xenia Fielding-Clarke. They were both in their late eighties. Bernard was an intellectual, communist and clergyman and full of ideas. Xenia, was Russian, and very warm – excitable, and loving. They were generous in their interest in me, who knew so little and was inclined to idealism. Their large house 18th century house was darkened by the copper beech tree in the garden and dust lay thick on the furniture and rugs. There was a study full of books, and a basement kitchen, the table cluttered with newspapers and chipped crockery, cutlery encrusted with old food, as Xenia had all but lost her sight.

I remember when Xenia died, I went to visit Bernard. He was sitting alone in his study. Sweet-scented lilacs drooped over the desk. It was late afternoon and the sun was going down over the meadows. ‘I have been thinking about what I want to do with the rest of my life,’ he said. ‘It is important to be clear about the work I still want to do.’ Though I have long forgotten rest of the conversation, I have always remembered those words, and the fact that he wanted to tell me. It seemed to me both remarkable and significant. I have just finished reading Atal Gawande’s wonderful book, ‘Being Mortal,’ an uplifting, and at times harrowing read. It is about our attempt to find meaning, particularly in old age or through suffering and illness. What is a good death, he asks. He writes of his challenges as a medic, the mistakes he’s made in skirting around uncomfortable truths, and the wonderful transformations he’s witnessed in people when terminal illness is approached with honesty, sensitivity and courage. Seeing my parents retreat into very old age is an unsettling experience, a slow insistent and persistent grief. I can’t see an end that won’t bring more sadness, at least for a while. Sometimes, in order to keep buoyant, I find myself searching for meaning – a search more urgent when I’m at the lowest ebb. And meaning shifts and changes, sometimes disappears altogether – for better or worse. Love and friendship are essential, as well as movement and dance, and teaching others to find balance, strength and ease in the body. But though it doesn’t add up – being of little significance to anyone else – the days I manage to write are strangely illuminated. Why do I keep forgetting this need to grapple with words, sentences, character, and story – the need to listen ever more intently to the unconscious, to be truthful to what is heard, and to perfect the skills of interpretation? In a converted factory in one of the many courtyards near Hackescher Markt – Berlin-Mitte, is the home and art collection of Erica Hoffmann. It extends from the third to the fifth floor, round three sides of the courtyard – room after room of airy spaces, some white painted, others retaining the old worn paintwork of the factory. From the early 60s, Erica and Rolf Hoffmann were involved with many contemporary artists – leading them eventually to acquire an extensive collection of art in many different media. You can read about them here – Sammlung Hoffmann. Now that Rolf Hoffmann has died, Erica continues to add to the collection, and every July a new exhibition is mounted. Every Saturday she opens her home to the public.

It’s over a week since I returned from Berlin, but visiting Erica Hoffmann’s home was one of the highlights of my stay – as much for the experience of walking through those extensive rooms, as for the art itself. Wearing large wool slippers that slid along the wooden floors, we were led from room to room by our guide, who attempted to engage us in lively discussion about the pieces. I recall a tiny hole in the floorboard where, looking down, we saw the video work of Pipilotti Rist – Selbstlos im Lavabad – a blonde woman surrounded by flames, reaching her flailing arms towards us, crying for help – so tiny it was oddly amusing in a comic-book way. In another room the powerful work by Chiharu Shiota – Inside Outside – a tower created by old window frames and glass – a labyrinth of windows leading towards it – inside a single chair, evoking a sense of loneliness, isolation, the world through or beyond windows. There was so much to see and to wonder about that an hour and half was scarcely time for one room alone. From the huge windows we looked down to the courtyard café, the sunlight in the shimmering trees, over a wall to a metal fire escape winding down the side of a building, the many angles of rooftop and gable. I was struck by Erica’s library in a gallery at the top of the building – two high bookshelves running almost the length of the room, parallel and about ten feet apart – between them a chaise-long, a lamp, a table. Such simplicity and elegance, and so many art books. Leaving the building, full of images and ideas, I felt very up-lifted. I loved the building with its sense of space and peace, was intrigued by the work, but above all inspired by the Hoffmanns’ desire to create something so beautiful, and in so doing, support many artists, both financially, and in the sharing and development of their work. It is something, if ever I had money, I would dearly love to do. I’ve just returned from a weekend in Berlin visiting my son. I was last there twenty years ago with Amici Dance Theatre, performing for a week in the Akademie der Kunste, a piece called Ruckblick (or flashback). Ruckblick was about the life and work of the artist, Kathe Kollwitz, whose drawings and sculptures were hated by the Nazis for their portrayal of the suffering caused by poverty and war. It was an extraordinary week – emotionally and physically exhausting, at times very sad, at other times deliriously joyful. Ruckblick was created by Wolfgang Stange, who was born at the end of the war and brought up in West Berlin. His many works bear the stamp of someone haunted by Germany’s recent history, and trying to reconcile the weight of guilt. When Germany was divided by the wall, half of his family were living in the east, so, along with so many others, they were separated. He never thought that would change during his lifetime. It was five years after the wall had come down when we took Ruckblick to Berlin. Everything was still very raw. When we weren’t in the theatre rehearsing or performing, we were touring around a city that looked like a building site, or visiting buildings where hideous events had taken place – Wannsee, where the Nazis planned the fate of the Jews, and Plotzensee Memorial for the resistance workers who were hanged by the Nazis. I remember the bitter wind of April, and an aching sadness. That said, there were brilliant moments too – the camaraderie of the company, the great welcome we received from our hosts, roses falling from the fly-tower of the theatre after our last performance, and the late night walks back home, singing and dancing along the streets, past the river and parks. One evening a few of us were taken into East Berlin to visit an arts centre in an old school. It was the bleakest place, broken down, grey, cold, the wind and rain whipping around the corners of the blocks. We shivered as we were taken around, marvelling at the courage and resourcefulness of the artists who were trying to build a new world out of the rubble. Later, we huddled over hot chocolate in a little corner café. My son now lives in the east, in an area called Friedrichschain. The trams are bright yellow instead of grey, the streets are lined with trees, the buildings painted in many colours, as well as covered in graffiti. There are little shops, markets, and cafés everywhere – so much life and colour and vibrancy. We walked by the river alongside the remains of the wall – how can it have been such a flimsy construct – barely six inches thickness? We sat on the riverbank, in the sunlight, drinking beer, and I marvelled that this was the same city I visited twenty years ago. How successfully the ghosts are scribbled out. Or are they? |

AuthorTricia Durdey dances, writes, and teaches Pilates. Archives

October 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed