|

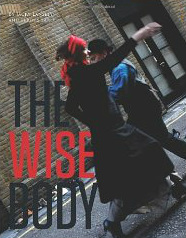

The Wise Body, compiled and written by Jacky Lansley and Fergus Early, celebrates the lives and work of twelve experienced older dancers. They are all dancers who began their career in childhood or youth, and who are still dancing into middle and later years. There is no question of retiring, or of becoming ‘too old,’ as society would have it. For all of them dance is a way of life; they have continued to grow through lifetime of dancing, and they continue to enrich the dance community-and beyond - with their work.

The Wise Body is formed of twelve chapters, with an introduction and afterthoughts. The beauty of the book is that each chapter takes the form of an interview with one of the dancers, sometimes recorded at different times over several years, giving a sense of time and depth to the writing. We’re given insights into ballet, Western contemporary dance, and the radical New dance of the 1960s and 70s, as well as dance that has its roots in tap, flamenco, Indian dance and non-dance forms of movement such as tai chi. Through their work the dancers have individually discovered links with theatre, poetry, music, philosophy, art and architecture, religion, and science. They speak with eloquence, revealing aspects of a rich world. This interview form also enables the reader to hear the unique voice of each dancer. Each chapter is far more than a mini-memoir or discourse into the dancer’s thoughts on dance. In a sense their words become the dance – from the highly energetic, almost chaotic flow of memory in Will Gaines interview, to the thoughtful meditative words of Pauline de Groot, or the searching, intense scrutiny of Steve Paxton. We see clearly what it is that excites each dancer, and we sense the profound connection between mind, body and imagination experienced by them all. In their epilogue Jacky Lansley and Fergus Early state how important this book may be for young dancers, giving them a strong sense of lineage, a foundation to their own work. It is also for the many experienced dancers in the world – those who might have retired from performing, as well as those still engaged with it, connecting them to their roots. Finally it is for those who have watched dance many times and wondered what it feels like to dance – to have lived a life through dance. This is a beautiful book, powerfully life affirming. ‘Do you think dance is important to the world?’ the interviewers ask each dancer. The answer is yes.

0 Comments

I always remember the children’s writer Jan Mark on an Arvon Foundation

course reminding us to ‘make a daily appointment with your desk.’ Some days we might feel stuck and frustrated and barely able to write a paragraph, but the appointment is a kind of act of faith that the next day the ideas will flow. There is also movement. I’m always struck by the connections between writing and moving, never more so than those days when I sit at my desk and dream, and very little work is produced. Even the simple act of getting up to make tea might enable some connection to be made so I can speed on for a while when I return to the desk. But the strangest thing is that after I’ve stopped writing for the day and I’m out walking out in the fields, the ideas, images, and particularly the voices of my characters are guaranteed to flood in so powerfully it’s as if a film is playing in my head. Then I wish there were some kind of recording mechanism in the mind. I often think I’ll remember, only to find I don’t quite get it as it was in that glorious moment and I need a notebook to scribble the words as fast as they flow. I love the way one activity enables freedom in another – the way narrative seems to have its own momentum long after I’ve stopped trying – the unconscious connection between movement and imagination. The other day I came across an old postcard with this photograph of Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham in Graham’s ballet Letter to the World. It was sent to me many years ago by my friend Claire Glaskin, who was tragically killed in a car accident in 2009. We were then in our twenties and Claire was yet to become internationally known as a choreographer for opera. On the back of the postcard Claire had written,

I’ve just performed this leap with my soul. Most extraordinary. I dread it in the move towards it, am terrified in the act of it and only afterwards know the joy of it. Did Merce Cunningham feel the same way I wonder? Letter to the World, a biographical dance-drama created in 1940, was based on the life and work of Emily Dickinson, and launched Martha Graham as one of the icons of contemporary dance – before then she was very much the outsider struggling for recognition. At the time of its creation I think Graham felt a strong affinity with the isolated New England poet. She was firmly convinced that the artist must turn away from the world, forgo marriage and children in order to achieve anything. Only then, out of struggle and isolation, could great art be born. I’ve never been enamoured by the romantic notion that art must spring from sacrifice and suffering. Surely inspiration can be nurtured in the hurly burly of family life, creativity snatched in moments between child-rearing, or tending older parents? I’m not sure the average artist 'suffers’ any more than someone in a nine to five office job? Isn’t he or she in a privileged position anyway to be able to devote all the time in the world to art, albeit in a state of poverty? There is of course rigour and determination, as well as time, required to master the craft of choreographer or writing, as well as tenacity to push through limitation and mediocrity. There is fear of failure and humiliation, as well as days when we just can’t be bothered with the whole damn thing. But I think in the end the pleasure in making work outweighs all this. If Claire were still alive, as a mature artist I think she would experience joy mid-leap as well as afterwards, and I’m sure that Cunningham did. |

AuthorTricia Durdey dances, writes, and teaches Pilates. Archives

October 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed