|

There’s a place in Staffordshire where the road to Biddulph Moor turns in the direction of Leek, and dropping downhill the whole vast land of field and hedge and hill seems to open before you far into the distance where, almost imperceptibly, it meets the sky. It was here on a sunny Wednesday afternoon in September 2011 that I first met John Ivor Sutton.

I was on my way back from a rehearsal in Crewe, and was heading for Parwich in Derbyshire where I was teaching later that afternoon. I’d just crested the hill, and the lane curved down between steep grassy banks. As I negotiated a narrow bend I passed an old man in a blue gabardine raincoat hitching from the verge. I was driving slow enough to stop so I picked him up. He wanted to go to the co-op in Leek for his weekly shop. He began to talk the moment he’d settled into the car... So begins the memoir I’m writing of Ivor Sutton, who died on November 19th 2012, Meetings with Ivor. Last week we headed back over the hills into Staffordshire to take photographs of Ivor’s house, now empty. The weather has been windy and wet, but the sun appeared and the wild empty hills, trees softly brown and gold, lay under a silvery light. We wandered around the paddock, past the chicken coops, gazing into the empty room where he’d lived almost all his life. His furniture lay rotting outside, and one ornament – a porcelain couple painted in gaudy colours, had been placed on the glass cabinet where Ivor once crammed his many knick-knacks. We drove on to Horton Church of St Michael and All Angels, where we buried Ivor on 30th November, in the churchyard with its majestic views over the hills. Not far from Ivor’s grave with its simple wooden cross, I discovered the grave of his mother. Ursula Alice, beloved wife of Richard Sutton, Royal Shop Biddulph Moor, Died May 15th 1925 aged 28. Not our will o lord but thine. Alice died of puerperal fever a month after giving birth to Ivor – so he told me the day I met him – and his father disappeared, mad with grief. He was brought up by his grandparents, the Farrals – richest farmers in the Staffordshire Moorlands. Ivor haunts me still, old rogue that he was, in a benign but insistent way – demanding that I tell what I can of his story – that I don’t stop with a straightforward account of our meetings over the course of a year, but go further and find what I can about his mother, Alice, and his father – the waggoner, Richard Sutton, who was poor but had money enough to pay for Alice’s ornate marble headstone before disappearing for forty years. Surrounded as I am at the moment with old age and too much death, I’m aware of the fragility as well as the robustness of life – the traces we leave behind, for a brief moment, before they’re gone forever.

4 Comments

Teaching today – my first class of the week - I’m aware of an empty space in the room, and I hesitate, not knowing quite how to begin – whether to talk about Jenny, who died last week of stomach cancer – or to wait until the last exercise. In the end I wait. All through class I’m aware of her, remembering the way she always chose to lie on the same spot on the floor by the radiator, how she wore wonderful hand-knitted socks that slipped off her feet in the down dog position, how supple she was showing years of yoga training before she ever came to Pilates. I never thought of her as old, though she’d accumulated years - a life that seemed rich with people and travel and art. She was beautiful too - and like many women who’ve been beautiful all their lives, she was Queenly. She commanded attention. Now she has gone.

I taught Pilates to Jenny for a number of years, both in big classes, and after she broke her ankle last year, alone in my studio. Over the last month, as she grew weaker, as we all knew there was little time left, I became aware, perhaps more profoundly than ever before, of the particular intimacy in teaching movement. As a movement teacher I know my students so well, at the same time as knowing so little about their lives. I know them purely through their body – observing how they look and how they move, and the changes that take place from week to week. It’s an intimacy that has clearly defined roles – I cajole, nudge, assist my class members to become stronger, more balanced, to enjoy moving and feel more at home in the body. At the same time, by interpreting and embodying my instructions, they teach me in ways that endlessly enrich my life. Waking in the night I felt shocked by the closeness of death. What was happening to Jenny as the cancer overtook her body? How could she just disappear forever? The night can be strange and difficult, and thoughts irrational. Arriving home after the last time I sat with Jenny, only days ago a beautiful restful hour I’d been reluctant to leave - I discovered the Morning Glory in the greenhouse had flowered at last. I’d waited all summer as it grew ever longer vines with not a bud in sight, and suddenly, on October 10th, there was this dazzling flower, its petals like sky blue silk, it’s centre radiant. Jenny always loved the last exercise we do in class, a calf stretch that ends in a balance with arms reaching overhead. It’s the only exercise we ever do in unison, in a circle, the arms sweeping up as if gathering and scattering the energy. Today, as we finished class with this gesture, sensing Jenny’s absence and presence, the shared sadness, and appreciation of her was palpable. She gave me much. I will miss her. A new ‘follower’ on Twitter posted this youtube clip of Wilson and Keppel and their Sand Dance. I’d never seen Wilson and Keppel before though I know two black and white cats named after them. Their dance is such fun. Bring back the Music Hall. It must have been a great night out.

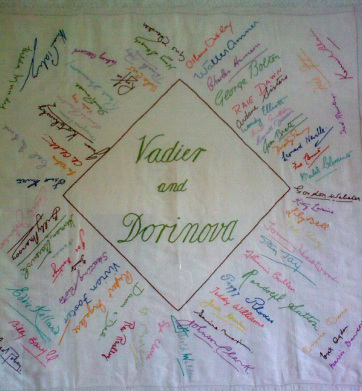

It made me think of my cousin who died long ago, Doreen Shaw Dorinova, who danced with her partner Vadier in Clements Variety Show. In those days legitimate dancers had to have a Russian sounding name. I wish I could go back seventy years and meet Dorinova as a young woman, or even find someone who can tell me about her life. She was a frail woman who began ballet classes to strengthen her legs after rickets. Apparently she wrote a memoir, but it was left with a ‘boyfriend’ and disappeared from the family. The only memory I have is of a tiny lady in a fur coat smiling over my pram. She gave me a gold chain bracelet and a rabbit fur cape I adored and was allowed to wear on special occasions. Doreen’s mother Auntie Carrie was much disapproved of by my mother’s farming family. There’s a marvellous photograph of her in a strapless dress, smiling over her shoulder at the photographer, little curls plastered to her forehead. I thought she was so pretty. Uncle Ernest, Doreen’s father, had a paper eye painted in lurid colours. It fascinated me when I was little and I remember wondering if it worked. Sometimes there was just a wodge of cotton wool in his eye socket. Doreen also spent much time embroidering. My sister has an elaborate screen, much shredded by my grandmother’s cats, embroidered with a rustic scene of deer by a stream, surrounded by strange trees looking like green clouds. I have this tablecloth. Around the edges are the signatures of all the people Doreen worked with - performers far more famous than Vadier or Dorinova. I like to think of her picking it up to stitch away between the acts. My cousin posted this extraordinary poem by Kay Ryan on his blog, Nigeness, last week.

AGE As some people age they kinden. The apertures of their eyes widen. I do not think they weaken; I think something weak strengthens until they are more and more it, like letting in heaven. But other people are mussels or clams, frightened. Steam or knife blades mean open. They hear heaven, they think boiled or broken. I love this poem and felt such elation reading it. She expresses with such clarity something I’ve observed in older people over the years – how age brings the opportunity to strengthen, to grow into our true nature. A long time ago I was talking about aging and what we would do with those years with a very close friend – a Buddhist. She talked of how she would spend the later part of her life seeking teachings about death and dying in preparation for death. I remember feeling perturbed by this – it seemed to me vital to live life to the full, not to spend years in the contemplation of death. I was afraid to challenge her. I reasoned that not being a Buddhist in any shape or form, I wouldn’t understand these things. My mother-in-law, Elizabeth, lived with a zest and exuberance that was unmatchable. She loved people, new places, red wine, cooking, and a good story – everything that was physical, of the world. She would not have time for such spiritual attendances. In the 50s and 60s she worked in Children’s Television, pulling the strings on Andy Pandy, Muffin the Mule, and many other characters. I can still see her standing in the middle of her kitchen in Co Durham, legs planted firmly on the floor, one hand on her hip, the other flourishing a large glass of red wine. Cheers darlings. She had such vitality – four boys – twins born in front of a delegation of student medics, two husbands, numerous large dogs – and an art degree awarded in her late seventies. Hers was the most beautiful death I’ve witnessed. She had throat cancer, did her best to find treatment, but when she knew it was untreatable and time was short, she continued to live to the full. She’d always loved food and could no longer eat anything, but she still made sure that everyone sat down to a hearty meal with much drink. She became bone thin – the last time I saw her a week before she died she’d been to see Noises Off at Birmingham Rep, and had then gone shopping for a new bra. The only ones that fitted her diminished frame were for young girls. She was beautiful in her white trousers and shirt embroidered with delicate colours – a fragility I’d never seen in her before - sitting out in the June sunshine, sucking on an Ice Pop regaling old tales, still the Queen of the family. Three days before her death, when she could no longer even take water except for a fine spray on her lips, she begged the medics to allow her to have morphine. She fought and won. On her death bed, between the hours of unconsciousness, she sang along to her new Shirley Bassey CD, wept a little that she was leaving us all, and radiated love that filled the house with quietness and light. It was an extraordinary gift she gave, especially to her children – my husband and three brothers in law – and to us, the extended family. She showed by example how to live and how to die - at the moment of her death the ‘apertures of our eyes’ and our hearts opened. I was away in London dancing at the time. I felt it. Grief came but was not harsh or unbearable. We were filled with elation that carried us through the year. |

AuthorTricia Durdey dances, writes, and teaches Pilates. Archives

October 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed